| The review consists of : |

|

The South Fork is ground from 0.110" thick S30V stainless steel, uniformly

hardened to 60 HRC (HRC tested) with a full cryogenic quench. The overall length

is 10.1 inches, with a sharpened edge of 4.6 inches on a blade which is 1.1

inches wide at maximum. The primary grind is full flat with an extreme distal

taper. The edge is very thin, from 0.006-0.008" thick, and ground at 14-16

degrees per side. The blade was tested for edge retention and durability by Phil

by whittling redwood, oak and making over 200 slices on half inch manilla.

The South Fork is ground from 0.110" thick S30V stainless steel, uniformly

hardened to 60 HRC (HRC tested) with a full cryogenic quench. The overall length

is 10.1 inches, with a sharpened edge of 4.6 inches on a blade which is 1.1

inches wide at maximum. The primary grind is full flat with an extreme distal

taper. The edge is very thin, from 0.006-0.008" thick, and ground at 14-16

degrees per side. The blade was tested for edge retention and durability by Phil

by whittling redwood, oak and making over 200 slices on half inch manilla.

With the origional edge profile and finished with a 1200 grit DMT hone, the South Fork push cut through hemp with 21.5 (5) lbs and made a slice with 9.5 (5) lbs, showing high aggression. With the edge refined by five passes per side on chromium oxide loaded leather, the cutting ability improved to 7.5 (5) and 17.5 (5) lbs respectively. With continued work on the loaded leather the performance maximized at 6.5 (5) and 12.5 (5) lbs respectively. This was after a total of 20 passes per side. At this point the edge was slipping a little on the two inch slice, however the push cutting sharpness was so high it was still sinking readily through the rope. At this point the South Fork took 90 (5) grams to cut the light baisting thread and 1.35 (5) centimeters to cut the light cotton under a 100 gram load, only 0.25 centimeters under a 200 gram load. The knife easily shaved, and caught hair above the skin, and would slice paper towel smoothly. Further work with sharpening which improved the cutting performance on hemp can be seen below.

The South Fork features to a very slim point due to the thin stock, high flat grind and full distal taper. The tip was still rigid enough to take a 50 lbs push into a phonebook and not require hand support such as on Catcherman. The South Fork sank to a depth of 284 (11) pages into a phone book with the edge with a rough finish from a silicon carbide stone. The point is too slim due to the distal taper to do a heavy stab, extreme control would be required to prevent the point from bending during the impact. With the edge highly polished the point penetration increased to 305 (20) pages.

The South Fork worked very well

as a paring knife. Though a little long, it was nice and light in hand and very

comfortable through extended use.

The efficient cutting geometry allowed it to cut into vegetables readily and

the narrow blade efficiently turned while peeling potatos. It also deftly

separated the rind from melons and cored apples with the precise point.

The South Fork worked very well

as a paring knife. Though a little long, it was nice and light in hand and very

comfortable through extended use.

The efficient cutting geometry allowed it to cut into vegetables readily and

the narrow blade efficiently turned while peeling potatos. It also deftly

separated the rind from melons and cored apples with the precise point.

| As a light utility knife, The South Fork would slice through potatos without moving the needle on a scale so it didn't even requiring a significant fraction of a pound to make the cuts. On carrots it matched the performance of the chisel ground utility knife from Lee Valley which sets an optimal standard for utility kitchen knives. Both knives both required minimal force of 1-3 lbs to make the slices. In general the more significant dropped blade profiles do make rapid dicing more efficient and allow rocking of the blades for fast mincing such as found on chef's knives but such profiles reduce blade versatility in general over the more utility based pattern of the South Fork. In general the performance of the South Fork compared well to many knives for such work is often many to one in favor of the South Fork due to the very slim blade and thin and acute edge. |

|

|

|

|

The RSK and Ratweiler are both generally well respected in terms of cutting ability, for their class of knife. They are included to show just how far the South Fork is optomized in that regard. The Heafner Bowie is more of a tactical design with a heavier main profile. This tradeoff of cutting ability in general is made so as to allow the knives to be used as general utility tools and usually to allow significant prying. This force difference holds across other materials such as ropes, carboard or wood, specific to foods, it increases with the size of the vegetables. Cutting up turnips the advantage of a much more slender cross section is even more obvious.

The South

Fork works well on meats, easily slicing up some pork rind. It also has

enough length for larger cuts of meats, cutting steaks and trimming a salmon

for stock. The very fine tip goes into the fish well and the edge has no

problems making the heavier cuts through bones.

The grip is highly reflective in several of the above pictures as the

security was examined by coating the handle with olive oil to see if there would

be problems with control, none were found.

The South

Fork works well on meats, easily slicing up some pork rind. It also has

enough length for larger cuts of meats, cutting steaks and trimming a salmon

for stock. The very fine tip goes into the fish well and the edge has no

problems making the heavier cuts through bones.

The grip is highly reflective in several of the above pictures as the

security was examined by coating the handle with olive oil to see if there would

be problems with control, none were found.

Carving woods, the South Fork performs well due to the high

flat grind and thin and acute edge. For such work a high polish is optimal and

when so sharpened the South Fork both cuts off very thin sections of soft and

hard woods which are nearly paper thin and at the same time is capable of

hogging off thick sections for roughing wood to shape for stakes or general

carving projects. It is a very nice blade for such work being very light in hand

and the narrow blade turns well so it cuts curves well.

Carving woods, the South Fork performs well due to the high

flat grind and thin and acute edge. For such work a high polish is optimal and

when so sharpened the South Fork both cuts off very thin sections of soft and

hard woods which are nearly paper thin and at the same time is capable of

hogging off thick sections for roughing wood to shape for stakes or general

carving projects. It is a very nice blade for such work being very light in hand

and the narrow blade turns well so it cuts curves well.

|

The South Fork also readily removes the dried bark from larger pieces of wood

which can be used for firestarting in many ways; shingles to keep the embers off

the cold/wet ground, it can be scraped for tinder and burnt directly. Removing

the bark also allows the wood to dry out much faster which is important for a

long term perspective. Bark with a very high pitch content can also be used to

make glue by heating it and adding

ash/animal scat and is excellent for firestarting as it will burn hot for an extended period of time (like half an hour) and can dry out small wet woods.

As this isn't a prybar type knife the bark is cut and worked off rather than chopped/pried off rapidly as it would be with a larger knife like the Ratweiler. If a lot of bark has to be removed or it is really heavy a bark spud can be carved out of a small piece of wood to make the process more efficient. A bark spud is simply a sharpened piece of steel used to slide under the bark and pry it off, the tip is rounded to prevent the bark from being cut. They can also be made out of hard woods in a few minutes with a decent knife. They can be just carved to shape but it is usually more efficient to split a small piece of wood which reduces the need to hog off a massive amount of shavings. Splitting the wood in general is a good ideal for most tool construction because not only does it save time in minimizing waste removal, it als gives multiple pieces of large stock to work with. Since the South Fork has a very slim profile and a very thin and acute edge, care needs to be taken during the batoning to avoid hitting the tip and not chisel cut through knots. Note the large knot on the bottom of the wood being split to the right, this was why the split was started at the other end. It took about 250 taps to drive the knife through the piece of birch far enough so that it could be pulled apart by hand. It is a simple matter then to carve a spud in a couple of minutes. This spud can be used very aggressively to remove thick barks. Unless it is fire hardened or very hard wood it will get dented up in use but it is a simple matter to resharpen it as necessary with the knife. |

|

| |

| |

|

|

If a lot of heavy bark

has to be removed from standing trees or fallen logs a

different type of spud is more efficient.

Using a fork in the wood from a branch, a hook shape

can be made which allows the spud to be used with pull which is easier

physically. The hook spud on the right

was rough chopped to shape with a

Ratweiler. In general heavier chopping knives or

a small axe can

rough wood to shape much quicker than even the most efficient

carving knives can just slice off waste wood. This is a many to one advantage.

The birch on the right of the spud is the piece of wood just below the

wood which was used to make the bark spud.

A decent chopping took will readily chop off

all that waste wood in

just a couple of minutes. A saw can also be used to make the process more efficient than just carving is a chopping tool isn't available. Make a series of cuts into the wood which will weaken the wood and it will crack off readily.

With the basic profile roughly shaped with the larger knife, the South Fork is used then to smooth out the profile making it much more ergonomic and thin out the two edges. It does this much more efficiently than the Ratweiler as the South Fork has a thinner blade profile and thus higher cutting ability. The benefits of the two edges on this spud is that they can also be differentially ground, similar to a double bitted axe. The bottom taper is shaped really fine which allows it to work off thinner barks such as birch which can be used for many things besides tinder and the top part is left fairly obtuse to handle removal of rough bark. |

|

| |

|

|

Breaking down larger woods, isn't an area in which the South Fork excells. It doesn't have the length nor the cross section to enable vigerous application of the necessary force to crack apart larger wood. Knives which do this well are much larger and thicker, blades like the Ratweiler a decent heavy machete like Barteaux, and as well of course solid axes like the Wildlife from Bruks. If this has to be done for burning or construction then it is of course still much easier with the South Fork than barehanded. The best method is to cut wedges which the South Fork carves very efficiently. Ideally these are hardwoods or at least harder than the wood being split. If they are too soft they will be compressed by the wood and not be able to split it. These wedges can be pounded into existing cracks in season or dead woods and crack the rounds apart directly. If the wedges are soft and weak and the wood being split is very hard then it may be necessary to instead to split a piece off of the wood and use this to make a harder and stronger wedge. It may also be necessary to split the wood in sections. If there are no cracks started then the South Fork is ued to cut a notch into the face of the wood to start the wedge. It is usually necessary to reshape the edges during the splitting as the edges often get damaged. For this type of work in general a simpler steel is prefered to give greater toughness, the Sandvik steels are optimal for a stainless steel in that type of blade. |

|

|

| Aside from wood, there are more cutting chores in the winter, often snow and ice often need to be cut. Snow blocks can be used to make shelter or to make a more stable fire. If the snow is soft it can be dug out with the hands however if the snow has a top crust it can be so hard that a knife is very useful to cut through it. The South Fork does this readily using the tip to make the initial cut and then sawing to enlarge the cut and break the crust into blocks. The tip has a very slim design due to the distal taper the blocks are cut smaller until they break free, not leveraged loose. Of course a stick can also be cut for prying once the initial cuts are made though generally it won't get through the initial hard crust. The same general technique can be used to dig up or break apart ice. Again as the South Fork has a slim point the knife was not used as a jackhammer with violent stabs driving from the shoulder. The point was used with wrist pops to break apart the ice and the hole gradually enlarged working around the opening and taking advantage of the brittle nature of the ice to allow bigger pieces to be removed. The ice can of course be melted for water, or removed to allow a fire to be started on dry ground, or enable fishing. The ice can be shaped into a lens to allow fire starting by focusing the light from the sun, this is not easy to do. |

|

|

The South Fork works readily slices thin plastic, cutting through a

television remote case with almost no effort.

It also glides effortlessly through cardboard from thin sheet stock to 1/8

and even 1/4" ridged with barely any force. The limits of reading the scale

were about half a pound and the South Fork barely registed on the thinner

stock. The following table compares the performance to a couple of

different knives for reference. All blades were very sharp (beyond shaving)

before the cutting, the cuts were made on a slice through twice the blade

length so as to check for solid push cutting sharpness in addition to

slicing aggression :

The South Fork works readily slices thin plastic, cutting through a

television remote case with almost no effort.

It also glides effortlessly through cardboard from thin sheet stock to 1/8

and even 1/4" ridged with barely any force. The limits of reading the scale

were about half a pound and the South Fork barely registed on the thinner

stock. The following table compares the performance to a couple of

different knives for reference. All blades were very sharp (beyond shaving)

before the cutting, the cuts were made on a slice through twice the blade

length so as to check for solid push cutting sharpness in addition to

slicing aggression :

| knife | 1/8 cardboard | 1/4 cardboard | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| force | rank | force | rank | |

| lbs | lbs | |||

| South Fork | 0.5 | 10 | 1.0 | 10 |

| Mora 2000 | 5.0 | 1 | 7.0 | 1 |

| Ratweiler | 5.0 | 1 | 7.0 | 1 |

The Mora 2000 is a well regarded

single-bevel utility knife which works well as a wood carver, but the

nature of the grind is very binding on cardboard, similar to how machetes

bind in thick woods, and it is about ten to one behind the South Fork. The

Ratweiler is a much thicker small bowie and

interestingly enough is near idential to the Mora

2000 on the cardboard, as the Ratweiler's tapered profile due to the

high flat grind reduces binding. All these strips of cardboard were tied in bundles and covered with wax to make

ready burn logs which allow firestarting in

harsh conditions.

The Mora 2000 is a well regarded

single-bevel utility knife which works well as a wood carver, but the

nature of the grind is very binding on cardboard, similar to how machetes

bind in thick woods, and it is about ten to one behind the South Fork. The

Ratweiler is a much thicker small bowie and

interestingly enough is near idential to the Mora

2000 on the cardboard, as the Ratweiler's tapered profile due to the

high flat grind reduces binding. All these strips of cardboard were tied in bundles and covered with wax to make

ready burn logs which allow firestarting in

harsh conditions.

In general, the South Fork works well over a wide range of material, the

cutting ability is high due to the slim profile from the combination of thin

stock, full high flat grind, distal taper and thin and acute edge.

It cut styrofoam very thin, almost transparent, went through a used

sandal with 5-7 lbs to cut on a draw through the entire blade length, the South

Fork was very aggressive on the slice, no slipping along the thick rubber. It slices up plywood with no damage (under 10x magnification). It also was used to

split pine with hand force of 9-11 lbs and a rocking motion to start the

cut. The birch hardwood splitting was required more force, 44 (2)

lbs to make a split, care was taken to

prevent twisting of the blade. Some television

cable took 31-35 lbs on a trocking press cut.

In general, the South Fork works well over a wide range of material, the

cutting ability is high due to the slim profile from the combination of thin

stock, full high flat grind, distal taper and thin and acute edge.

It cut styrofoam very thin, almost transparent, went through a used

sandal with 5-7 lbs to cut on a draw through the entire blade length, the South

Fork was very aggressive on the slice, no slipping along the thick rubber. It slices up plywood with no damage (under 10x magnification). It also was used to

split pine with hand force of 9-11 lbs and a rocking motion to start the

cut. The birch hardwood splitting was required more force, 44 (2)

lbs to make a split, care was taken to

prevent twisting of the blade. Some television

cable took 31-35 lbs on a trocking press cut.

On cardboard, as a first rough check, the South Fork was compared to a Coyote Meadow and Blackjack small on 1/4" stock with cuts made on a slice through 3 centimeters of blade. The primary edges were cut to 8-12 degrees per side and a final microbevel applied with the fine rods of the Sharpmaker set at 20 degrees per side. The sharpness was measured by cutting light cotton at 200 grams of tension intially and switched to 400 grams during the last two rounds as the blunting was fairly severe.

| Knife | steel | hardness | Cardboard | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 m | 3.1 m | 9.3 m | 15.8 m | |||

| HRC | 200 g | 400 g | ||||

| South Fork | S30V | 60 | 23 (3) | 232 (17) | 139 ( 9) | 206 (11) |

| Coyote Meadow | 10V | 62.5 | 21 (2) | 218 (14) | 113 ( 9) | 188 (11) |

| Blackjack small | 52100 | NA | 29 (3) | 200 (12) | 207 (12) | 329 (16) |

Even this rough work, just the average of two runs, was enough to show a large difference between the South Fork, Coyote Meadow and the Blackjack small . The Blackjack was not in the same class as ther other two blades both in initial sharpness and especially in edge retention. To verify the results more cardboard was cut, 1/8" thick, again cuts were made on a slice through three centimeters of blade. This time the final microbevel was set with the medium Sharpmaker rods at 20 degrees, the tension in the cord was 200 grams for all of the cutting for ease of comparison.

| Knife | Cardboard | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 m | 3.9 m | 10.0 m | 21.5 m | |

| 200 g | ||||

| South Fork | 25 (2) | 110 ( 8) | 173 (16) | 235 ( 9) |

| Coyote Meadow | 35 (2) | 135 ( 9) | 198 (10) | 225 (10) |

| Blackjack small | 33 (2) | 290 (23) | 525 (49) | 750 (66) |

This was an average of four runs with the initial edge set with a 200 grit silicon carbide waterstone and then polished with a 1000 grit alunimum oxide waterstone and then the microbevels applied with the Sharpmaker. With each subsequent round the microbevel bevels were just recut with the Sharpmaker, the primary edge was not recut.

To see if the nature of the abrasive was an influence, specifically if the hardness of the vanadium carbide required a harder sharpening abrasive, another round of cardboard was cut. This time 0.160" thick stock was used and the microbevel applied with a 600 grit DMT 12" rod. Again the tension in the cotton was kept to a uniform 200 grams.

| Knife | Cardboard | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 m | 1.6 m | 4.6 m | 17.1 m | |

| 200 g | ||||

| South Fork | 35 (2) | 60 (3) | 140 ( 6) | 225 (17) |

| Coyote Meadow | 40 (2) | 65 (3) | 150 ( 5) | 200 (10) |

| Blackjack small | 43 (3) | 78 (4) | 325 (20) | 588 (41) |

The results are similar to the previous run, again the Coyote Meadow is shead of the South Fork, however the blades are very close, and both are massively ahead of the Blackjack small, being able to cut many times more cardboard before the same extent of blunting is noticed. This performance difference is so large little precision is needed to benchmark it, the Blackjack small starts ripping the cardboard towards the end while the other two blades still cut it smoothly. There also seems to be a large difference in how the blades are blunting in that the rate seems to be fairly constant for the 52100 Blackjack by the higher alloy blades from Wilson seem see a reduced rate of blunting towards the end of the cutting. To check this in more detail more work was done and the sharpness checked more frequently.

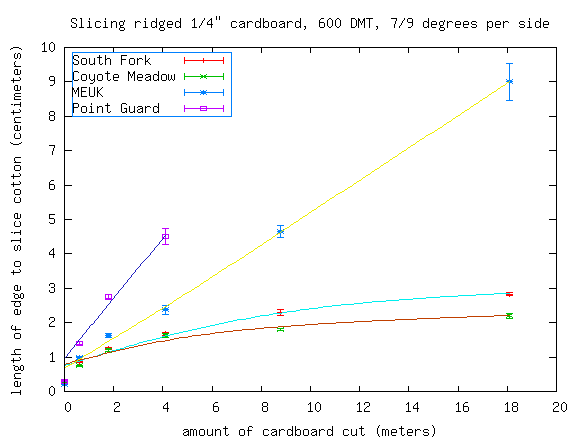

As as a consistency check on 52100 another 52100 blade was used as a reference, a MEUK which was forged and heat treated by Ed Caffrey to an edge hardness of 57/59 HRC with a softer spine. A Point Guard in 420J2 stainless (54/56 HRC) was used as a low end benchmark. The cardboard used was 1/4" thick, double layered, the edges on the knives were all set to 7/9 degrees per side, a reduced angle to see if any difference was noted as this should enhance the relative performance of the harder blades especially. The edges were honed freehand on a 600 DMT stone, no microbevel, then cleaned with 3 passes per side on leather loaded with chromium/aluminum oxide, then the same on plain leather and finally again on newsprint. The sharpness was measured cutting light cotton under 200 grams of tension as well as slicing and push cutting newsprint.

| Knife | Cardboard | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 m | 0.6 m | 1.8 m | 4.1 m | 8.8 m | 18.1 m | |

| 200 g | ||||||

| South Fork | 20 (1) | 85 (2) | 125 (3) | 168 ( 4) | 230 ( 8) | 283 ( 5) |

| Coyote Meadow | 25 (1) | 75 (2) | 120 (4) | 163 ( 6) | 180 ( 4) | 220 ( 7) |

| MEUK | 20 (1) | 98 (4) | 163 (5) | 238 (13) | 465 (18) | 900 (54) |

| Point Guard | 30 (1) | 140 (4) | 275 (8) | 450 (24) | ||

With the reduced edge angle the Coyote Meadow had a pronounced increase in edge retention over the South Fork. The initial sharpness of all blades is much higher than with the 600 DMT rod, which may show the advantage of the flat benchstone over the rod due to lower pressure and resulting minimization of burr formation. Note the massive increase in edge retention over the 1/4" cardboard trial with the microbevel at 20 degrees on the fine Sharpmaker rods. With the edge reduced and the finished left more coarse the two Wilson blades cut six times as much cardboard before having a similar level of blunting being induced.

What is more interesting than the Coyote Meadow having an advantage over the South Fork, which would be expected given it is harder with higher wear resistance, is that the behavior of those blades is radically different than the MEUK and Point Guard which keep blunting at a linear rate while the two Wilson blades fall off in a logarithmic manner. Phil proposed the idea several years ago that this is due to the dependance of long term edge retention being influenced by carbides in those types of steels and the initial loss of edge retention being mainly due to deformation. This seems to be strong evidence for this hypothesis. This is seen more clearly in the following graph :

This also clearly shows that the difference in behavior as the Point Guard

and MEUK have a very different responce in extended cutting. Towards the end

the Wilson blades are starting to separate and the MEUK and Point Guard are

radically outclassed. The behavior is now tending to fall in line with standard

ASM ratios for wear resistance which is interesting. At the end of the cutting

(note not all blades were stopped at the same point) all blades could still

slice newsprint readily and in fact could do rough push cutting if held on an

angle if the cut was started. What was interesting is that while the slicing

aggression of the MEUK was radically lower than the other two blades, on

newsprint it was quite close maybe showing the problems with point measurements

of sharpness. However the cotton cutting correlated very well to the cardboard

cutting because it correlated quite well to the point at which the MEUK and

Point Guard would tear the cardboard (past 4 and 9 meters respectively) :

This also clearly shows that the difference in behavior as the Point Guard

and MEUK have a very different responce in extended cutting. Towards the end

the Wilson blades are starting to separate and the MEUK and Point Guard are

radically outclassed. The behavior is now tending to fall in line with standard

ASM ratios for wear resistance which is interesting. At the end of the cutting

(note not all blades were stopped at the same point) all blades could still

slice newsprint readily and in fact could do rough push cutting if held on an

angle if the cut was started. What was interesting is that while the slicing

aggression of the MEUK was radically lower than the other two blades, on

newsprint it was quite close maybe showing the problems with point measurements

of sharpness. However the cotton cutting correlated very well to the cardboard

cutting because it correlated quite well to the point at which the MEUK and

Point Guard would tear the cardboard (past 4 and 9 meters respectively) :

On plywood, the South Fork showed

strong edge retention, resisting edge damage and wear for an extended period of

time and could even make very thick cuts without damage. The performance was very different from the

small Sebenza also in S30V ground to the same edge angle

which shows that how a steel is hardened can significant influence the

performance.

On plywood, the South Fork showed

strong edge retention, resisting edge damage and wear for an extended period of

time and could even make very thick cuts without damage. The performance was very different from the

small Sebenza also in S30V ground to the same edge angle

which shows that how a steel is hardened can significant influence the

performance.

Though the grindability of S30V is fairly low which means that it takes longer to remove a given volume of metal, since the edge profile is so narrow and thin on the South Fork very little metal has to be removed because the area of the edge is so small. This minimization of edge greatly enhances ease of sharpening as does the acute initial edge angle which means it would respond rapidly to jigs and v-rods without need for reprofiling.

The South Fork was sharpened on a varity of abrasives to check the cutting ability on 3/8" hemp and see how it ranked on the thread and light cord cutting. A 6" DMT fine benchstone was used, a 1200 grit DMT diafold, 15 micron silicon carbide sandpaper, 0.3 micron aluminum oxide sandpaper, and 0.5 micron chromium/aluminum oxide loaded newspaper. All but the loaded newspaper were used with edge leading sharpening. The final edge angle was 10/12 degrees per side.

| Abrasive | thread | cotton | hemp | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 g | 200 g | slice | push | ||

| grams | centimeters (x100) | pounds | |||

| 600 DMT | 136 (13) | 65 ( 6) | 32 (3) | 7.0 | 17.5 |

| 1200 DMT | 118 (19) | 67 ( 3) | 32 (3) | 6.5 | 15.5 |

| 15 micron silicon carbide | 117 ( 7) | 80 ( 4) | 33 (2) | 6.5 | 10.0 |

| 0.3 micron alimumum oxide | 93 (12) | 160 (13) | 33 (4) | 5.5 | 11.0 |

| 0.5 micron chromium/aluminum oxide | 75 (13) | 121 (24) | 21 (4) | 4.5 | 9.5 |

The two sandpaper runs are less than optimal as it was difficult to hone into the paper without the edge of the knife cutting through the abrasive. Even though the chromium/aluminum oxide finish has lower edge aggression under low tension on the cotton, it does very well under high tension and slicing the hemp, this is due to the slices essentially becoming push cuts at high forces due to the extreme push cutting sharpness. Those results all use fairly high end and modern abrasives so the question could be asked, can such high alloy steels such as S30V be sharpened well with inexpensive and more traditional abrasives. To investigate this the South Fork was sharpened free hand at 7.7 (2) degrees per side with no microbevel, and left with the finish of the following hones :

| Abrasive | thread | cotton | hemp | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 g | 200 g | slice | push | ||

| grams | centimeters (x100) | pounds | |||

| Coarse aluminum oxide | 112 (11) | 62 ( 5) | 29 (2) | 7.5 | 15.5 |

| fine aluminum oxide | 90 ( 5) | 42 ( 3) | 23 (1) | 5.5 | 12.5 |

| soft white arkansas | 100 ( 7) | 50 ( 4) | 26 (2) | 5.5 | 12.5 |

| black hard arkansas | 89 ( 4) | 40 ( 2) | 24 (2) | 5.5 | 11.5 |

| 0.5 micron chromium/aluminum oxide | 65 ( 2) | 56 (7) | 28 (2) | 5.0 | 10.5 |

There is no problem achieving a very high level of sharpness, in fact the higher polishes are superior to the first group, this is mainly due to them all being benchstones and not having the difficulty of the tapes. Note the differene in the chromium/aluminum oxide finishes, this is because in the first table it was after the edge produced from the tapes which is less than optimal. Note the hemp results will be elevated in the second table as the edge angle has been reduced by around twenty percent, so as a rough estimate at equal sharpness, this would reduce the force requiried accordingly.

The handle of the South Fork fits well in the hand in a variety of grips due

to the gentle contouring and complete lack of any square edges. Comfort was high

even in extended use in very hard cutting with no hot spots of any kind.

The index finger cutout worked very well in general, this was one of the more

common grips used in a lot of the cutting as the ergonomics were solid in such

an overhand grip as the front of the handled flowed well and didn't end in any

squarish transitions. The spine is also nicely rounded which also enhanced grip

ergonomics in forward and overhand grips.

The handle of the South Fork fits well in the hand in a variety of grips due

to the gentle contouring and complete lack of any square edges. Comfort was high

even in extended use in very hard cutting with no hot spots of any kind.

The index finger cutout worked very well in general, this was one of the more

common grips used in a lot of the cutting as the ergonomics were solid in such

an overhand grip as the front of the handled flowed well and didn't end in any

squarish transitions. The spine is also nicely rounded which also enhanced grip

ergonomics in forward and overhand grips.

Though there is

no aggressive texture there were no problems with security in general mainly due

to the high cutting ability which means little opposing force. Even with the

handle lubricated with olive oil there was no problem using it for various

utility work and cutting in the kitchen.

In order to check the handle security in extremes the grip was lubricated with

olive oil and then pressed into a scale and there was no problem putting 40 lbs

into the handle without any slippage. Security in the other direction was

examined by attaching a 25 lbs lead weight onto the blade and with the handle

still lubricated the weight was lifted from the floor. Again there was no

slippage :

Though there is

no aggressive texture there were no problems with security in general mainly due

to the high cutting ability which means little opposing force. Even with the

handle lubricated with olive oil there was no problem using it for various

utility work and cutting in the kitchen.

In order to check the handle security in extremes the grip was lubricated with

olive oil and then pressed into a scale and there was no problem putting 40 lbs

into the handle without any slippage. Security in the other direction was

examined by attaching a 25 lbs lead weight onto the blade and with the handle

still lubricated the weight was lifted from the floor. Again there was no

slippage :

This was an evaluation piece, no sheath.

The South Fork combines very high cutting ability, point penetration and grip ergonomics into a very high performance working knife.

Comments can be emailed to cliffstamp[REMOVE]@cutleryscience.com or posted to :

More information on the South Fork and other Phil Wilson knives can be seen on the Seamount Knifeworks website.

Most of the pictures in the above are in the PhotoBucket album.

| Last updated : | 01 : 10 : 2006 |

| Originally written: | 01 : 05 : 2006 |